It’s shaping up to be a severe season for respiratory syncytial virus infections – one of the worst some doctors say they can remember. But even as babies struggling to breathe fill hospital beds across the United States, there may be a light ahead: After decades of disappointment, four new RSV vaccines may be nearing review by the US Food and Drug Administration, and more than a dozen others are in testing.

There’s also hope around a promising long-acting injection designed to be given right after birth to protect infants from the virus for as long as six months. In a recent clinical trial, the antibody shot was 75% effective at heading off RSV infections that required medical attention.

Experts say the therapies look so promising, they could end bad RSV seasons as we know them.

And the relief could come soon: Dr. Ashish Jha, who leads the White House Covid-19 Response Task Force, told CNN that he’s “hopeful” there will be an RSV vaccine by next fall.

Charlotte Brown jumped at the chance to enroll her own son, a squawky, active 10-month-old named James, in one of the vaccine trials this summer.

“As soon as he qualified, we were like ‘absolutely, we are in,’ ” Brown said.

Babies have to be at least 6 months old to enter the trial, which is testing a vaccine developed at the National Institutes of Health – the result of decades of scientific research.

Brown is a pediatrician who cares for hospitalized children at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, and she sees the ravages of RSV firsthand. A recent patient was in the back of her mind when she was signing up James for the study.

“I took care of a baby who was only a few months older than him and had had nine days of fever and was just absolutely pitiful and puny,” she said. Brown said his family felt helpless. “And I was like, ‘this is why we’re doing it. This single patient is why we’re doing this.’ “

Even before this year’s surge, RSV was the leading cause of infant hospitalizations in the US. The virus infects the lower lungs, where it causes a hacking cough and may lead to severe complications like pneumonia and inflammation of the tiny airways in the lungs called bronchiolitis.

Worldwide, RSV causes about 33 million infections in children under the age of 5 and hospitalizes 3.6 million annually. Nearly a quarter-million young children die each year from complications of their infections.

RSV also preys on seniors, leading to an estimated 159,000 hospitalizations and about 10,000 deaths a year in adults 65 and over, a burden roughly on par with influenza.

Despite this heavy toll, doctors haven’t had any new tools to head off RSV for more than two decades. The last therapy approved was in 1998. The monoclonal antibody, Synagis, is given monthly during RSV season to protect preemies and other high-risk babies.

Lessons learned after grave setback

The hunt for an effective way to protect against RSV stalled for decades after two children died in a disastrous vaccine trial in the 1960s.

That study tested a vaccine made with an RSV virus that had been chemically treated to render it inert and mixed with an ingredient called alum, to wake up the immune system and help it respond.

It was tested at clinical trial sites in the US between 1966 and 1968.

At first, everything looked good. The vaccine was tested in animals, who tolerated it well, and then given to children, who also appeared to respond well.

“Unfortunately, that fall, when RSV season started, many of the children that were vaccinated required hospitalization and got more severe RSV disease than what would have normally occurred,” said Steven Varga, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Iowa, who has been studying RSV for more than 20 years and is developing a nanoparticle vaccine against the virus.

A study published on the trial found that 80% of the vaccinated children who caught RSV later required hospitalization, compared with only 5% of the children who got a placebo. Two of the babies who had participated in the trial died.

The outcomes of the trial were a seismic shock to vaccine science. Efforts to develop new vaccines and treatments against RSV halted as researchers tried to untangle what went so wrong.

“The original vaccine studies were so devastatingly bad. They didn’t understand immunology well in those days, so everybody said ‘oh no, this ain’t gonna work.’ And it really was like it stopped things cold for 30, 40 years,” said Dr. Aaron Glatt, an infectious disease specialist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in New York.

Regulators re-evaluated the guardrails around clinical trials, putting new safety measures into place.

“It is in fact, in many ways, why we have some of the things that we have in place today to monitor vaccine safety,” Varga said.

Researchers at the clinical trial sites didn’t communicate with each other, Varga said, and so the US Food and Drug Administration put the publicly accessible Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System into place. Now, when an adverse event is reported at one clinical trial site, other sites are notified.

Another problem turned out to be how the vaccine was made.

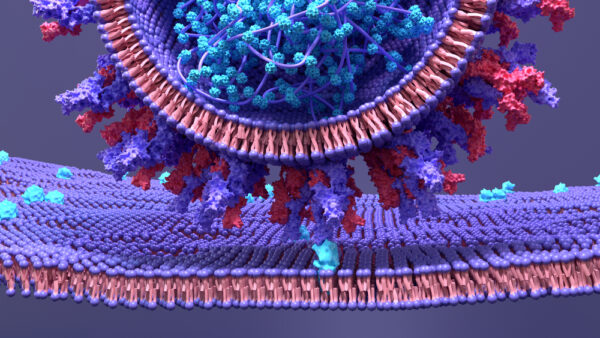

Proteins are three-dimensional structures. They are made of chains of building blocks called amino acids that fold into complex shapes, and their shapes determine how they work.

In the failed RSV vaccine trial, the chemical the researchers used to deactivate the virus denatured its proteins – essentially flattening them.

“Now you have a long sheet of acids but no more beautiful shapes,” said Ulla Buchholz, chief of the RNA Viruses Section at the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

“Everything that the immune system needs to form neutralizing antibodies that can block and block attachment and entry of this virus to the cell had been destroyed in that vaccine,” said Buchholz, who designed the RSV vaccine for toddlers that’s being tested at Vanderbilt and other US sites.

In the 1960s trial, the kids still made antibodies to the flattened viral proteins, but they were distorted. When the actual virus came along, these antibodies didn’t work as intended. Not only did they fail to recognize or block the virus, they triggered a powerful misdirected immune response that made the children much sicker, a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement of disease.

The investigators hadn’t spotted the enhancement in animal studies, Varga says, because the vaccinated animals weren’t later challenged with the live virus.

“So of course, we require now extensive animal testing of new vaccines before they’re ever put into humans, again, for that very reason of making sure that there aren’t early signs that a vaccine will be problematic,” Varga said.

A breakthrough reinvigorates the field

About 10 years ago, a team of researchers at the NIH – some of the same investigators who developed the first Covid-19 vaccines – reported what would turn out to be a pivotal advance.

They had isolated the structure of the virus’s F-protein, the site that lets it dock onto human cells. Normally, the F-protein flips back and forth, changing shapes after it attaches to a cell. The NIH researchers figured out to how freeze the F-protein into the shape it takes before it fuses with a cell.

This protein, when locked into place, allows the immune system to recognize the virus in the form it’s in when it first enters the body – and develop strong antibodies against it.

“The companies coming forward now, for the most part, are taking advantage of that discovery,” said Dr. Phil Dormitzer, a senior vice president of vaccine development at GlaxoSmithKline. “And now we have this new generation of vaccine candidates that perform far better than the old generation.”

The first vaccines up for FDA review will be given to adults: seniors and pregnant woman. Vaccination in pregnancy is meant to ultimately protect newborns – a group particularly vulnerable to the virus – via antibodies that cross the placenta.

Vaccines for children are a bit farther behind in development but moving through the pipeline, too.

Four companies have RSV vaccines for adults in the final phases of human trials: Pfizer and GSK are testing vaccines for pregnant women as well as seniors. Janssen and Bavarian Nordic are developing shots for seniors.

Pfizer and GSK use protein subunit vaccines, a more traditional kind of vaccine technology. Two other companies build on innovations made during the pandemic: Janssen – the vaccine division of Johnson & Johnson – relies on an adenoviral vector, the same kind of system that’s used in its Covid-19 vaccine, and Moderna has a vaccine for RSV in Phase 2 trials that uses mRNA technology.

So far, early results shared by some companies are promising. Janssen, Pfizer and GSK each appear effective at preventing infections in adults for the first RSV season after the vaccine.

In an August news release, Annaliesa Anderson, Pfizer’s chief scientific officer of Vaccine Research and Development, said she was “delighted” with the results. The company plans to submit its data to the FDA for approval this fall.

GSK has also wrapped up its Phase 3 trial for seniors. It recently presented the results at a medical conference, but full data hasn’t been peer reviewed or published in a medical journal. Early results show that this vaccine is 83% effective at preventing disease in the lower lungs of adults 60 and older. It appears to be even more protective – 94% – for severe RSV disease in those over 70 and those with underlying medical conditions.

“We are very pleased with these results,” Dormitzer told CNN. He said the company was moving “with all due haste” to get its results to the FDA for review.

“We’re confident enough that we’ve started manufacturing the actual commercial launch materials. So we have the bulk vaccine actually in the refrigerator, ready to supply when we are licensed,” he said.

Even as the company applies for licensure, GSK’s trial will continue for two more RSV seasons. Half the group getting the vaccine will be followed with no additional shots, while the other group will get annual boosters. The aim is to see which approach is most protective to guide future vaccination strategies.

Janssen’s vaccine for older adults appears to be about 70% to 80% effective in clinical trials so far, the company announced in December.

In a study on Pfizer’s vaccine for pregnant women published in the New England Journal of Medicine this year, the company reported that the mothers enrolled in the study made antibodies to the vaccine and that these antibodies crossed the placenta and were detected in umbilical cord blood just after birth.

The vaccines for pregnant women are meant to get newborns through their first RSV season. But not all newborns will benefit from those. Most maternal antibodies are passed to baby in the third trimester, so preemies may not be protected, even if mom gets the vaccine.

For vulnerable infants and those whose mothers decline to be vaccinated, Dr. Helen Chu, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Washington, says the long-acting antibody shot for newborns, called nirsevimab, should cover them for the first six months of life. She expects it to be a “game-changer.”

That shot, which has been developed by AstraZeneca, was recently recommended for approval in the European Union. It has not yet been approved in the United States.

Hope on the horizon

The field is so close to a new approval that public health officials say they’ve been asked to study up on the data.

Chu, who is also a member of an RSV study group of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, a panel that advises the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on its vaccine recommendations, says her group has started to evaluate the new vaccines – a sign that an FDA review is just around the corner.

No companies have yet announced that process is underway. FDA reviews can take several months, and then there are typically discussions and votes by FDA and CDC advisory groups before vaccines are made available.

“We’ve been working on this for several months now to start reviewing the data,” Chu said. “So I think this is imminent.”

Watching this year’s RSV season unfold, Brown, the pediatrician who enrolled her son in the vaccine trial for toddlers, says progress can’t come fast enough.

“The hospital is surging. We’re not drowning the way some states are. I mean, Connecticut, South Carolina, North Carolina, they’re really drowning. But our numbers are huge, and our services are so busy,” she says.

Brown says her son is mostly healthy. He doesn’t have any of the risks for severe RSV she sees with some of her patients, so she was happy to have a way to help others.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

And while it’s far too early to say whether the vaccine James is helping to test will prove to be effective, the trial was unblinded last week, and Brown learned that her son was in the group that got the active vaccine, not the placebo

He has done well through this heavy season of illness, she says. The NIH-sponsored study they participated in is scheduled to be completed next year.

The vaccine, which is made with a live but very weak version of virus, is given through a couple of squirts up the nose, so there are no needles. The hardest part for squirmy James, she said, was being held still.

“If we can do anything to move science forward and help another child, like, sorry, James. You had to have your blood drawn, but it absolutely was worth it.”

Health - Latest - Google News

October 31, 2022 at 06:52PM

https://ift.tt/XORfhNv

By the next RSV season, the US may have its first vaccine - CNN

Health - Latest - Google News

https://ift.tt/xMtFiBK