The US public health emergency declaration for mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, ends Tuesday.

The outbreak, which once seemed to be spiraling out of control, has quietly wound down. The virus isn’t completely gone, but for more than a month, the average number of daily new cases reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has hovered in the single digits, plummeting from an August peak of about 450 cases a day.

Still, the US led the world in cases during the 2022-23 outbreak. More than 30,000 people in the US have been diagnosed with mpox, including 23 who died.

Cases are also down across Europe, the Western Pacific and Asia but still rising in some South American countries, according to the latest data from the World Health Organization.

It wasn’t always a given that we’d get here. When mpox went global in 2022, doctors had too few doses of a new and unproven vaccine, an untested treatment, a dearth of diagnostic testing and a difficult line to walk in their messaging, which needed to be geared to an at-risk population that has been stigmatized and ignored in public health crises before.

Experts say the outbreak has taught the world a lot about this infection, which had only occasionally been seen outside Africa.

But even with so much learned, there are lingering mysteries too – like where this virus comes from and why it suddenly began to spread from the Central and West African countries where it’s usually found to more than 100 other nations.

How long has it been spreading?

Before May 2022, when clusters of people with unusual rashes began appearing in clinics in the UK and Europe, the country reporting the most cases of mpox was the Democratic Republic of Congo, or DRC.

There, cases have been steadily building since the 1970s, according to a study in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In the DRC, people in rural villages depend on wild animals for meat. Many mpox infections there are thought to be the result of contact with an animal to which the virus has adapted; this animal host is not known but is assumed to be a rodent.

For years, experts who studied African outbreaks observed a phenomenon known as stuttering chains of transmission: “infections that managed to transmit themselves or be transmitted from person to person to a limited degree, a certain number of links in that chain of transmission, and then suddenly just aren’t able to sustain themselves in humans,” said Stephen Morse, an epidemiologist at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

Informally, scientists kept track, and Morse says that for years, the record for links in a mpox chain was about four.

“Traditionally, it always burned itself out,” he said.

Then the chains started getting longer.

In 2017, Nigeria – which hadn’t had a confirmed case of mpox in more than four decades – suddenly saw a resurgence of the virus, with more than 200 cases reported that year.

“People have speculated maybe it was a change in the virus that allowed it to be made better-adapted to humans,” Morse said.

From 2018 through 2021, eight cases of mpox were reported outside Africa. All were in men ages 30 to 50, and all had traveled from Nigeria. Three reported that the rashes had started in their groin area. One went on to infect a health care provider. Another infected two family members.

This Nigerian outbreak helped experts realize that mpox could efficiently spread between people.

It also hinted that the infection could be sexually transmitted, but investigators couldn’t confirm this route of spread, possibly because of the stigma involved in sharing information about sexual contact.

In early May 2022, health officials in the UK began reporting confirmed cases of mpox. One of the people had recently traveled to Nigeria, but others had not, indicating that it was spreading in the community.

Later, other countries would report cases that had started even earlier, in April.

Investigators concluded that mpox had been silently spreading before they caught up to it.

Declaring an emergency

In early summer, as US case numbers began to grow, the public health response bore some uncomfortable similarities to the early days of Covid-19. People with suspicious rashes complained that it was too hard to get tested because a limited supply was being rationed. Because the virus had so rarely appeared outside certain countries in Africa, most doctors weren’t sure how to recognize mpox or how to test for it and didn’t understand all its routes of spread.

A new vaccine was available, and the government had placed orders for it, but most of those doses weren’t in the United States. Beyond that, its efficacy against mpox had been studied only in animals, so no one knew whether it would actually work in humans.

There was an experimental treatment, Tpoxx, but it too was unproven, and doctors could get it only after filling out reams of paperwork required by the government for compassionate use.

Some just gave up.

“Tpoxx was hard to get,” said Dr. Jeffrey Klausner, a clinical professor of public health at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

“I was scrambling to find places that could prescribe it because my own institution just became a bureaucratic nightmare. So I basically would be referring people for treatment outside my own institution to be able to get monkeypox treatment,” he said.

Finally, in August, the federal government declared a public health emergency. This allowed federal agencies to access pots of money set aside for emergencies. It also allows the government to shift funds from one purpose to another to help cover costs of the response – and it helped raise awareness among doctors that mpox was something to watch for.

The government also set up a task force led by Robert Fenton, a logistics expert from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, director of the CDC’s Division of HIV and AIDS Research.

Daskalakis is openly gay and sex-positive, right down to his Instagram account, which mixes suit-and-tie shots from White House briefings with photos revealing his many tattoos.

“Dr. Daskalakis … really walks on water in most of the gay community, and then [Fenton is] a logistics expert, and I think that combination of leadership was the right answer,” Klausner said.

Mpox as a sexually transmitted infection

Early on, after the CDC identified men who have sex with men as being at highest risk of infection, officials warned of close physical contact, the kind that often happens with sexual activity. They also noted that people could be infected through contact with contaminated surfaces like sheets or towels.

But they stopped short of calling it a sexually transmitted infection, a move that some saw as calculated.

“In this outbreak, in this time and context to Europe, United States and Australia, was definitely sexually transmitted,” said Klausner, who points out that many men got rashes on their genitals and that infectious virus was cultured in semen.

Klausner believes vague descriptions about how the virus spread were intentional, in order to garner resources needed for the response.

“People felt that if they called it an STD from the get-go, it was going to create stigma, and because of the stigma of the type of sex that was occurring – oral sex, anal sex, anal sex between same-sex male partners – there may not have been the same kind of federal response,” Klausner said. “So it was actually a political calculation to garner the resources necessary to have a substantial response to be vague about how it spread.”

This ambiguity created room for misinformation and confusion, said Tony Hoang, executive director of Equality California, a nonprofit advocacy group for LGBTQ civil rights.

“I think there was a balancing dance of not wanting to create stigma, in terms of who is actually the highest rates of transmission without being forthright,” Hoang said.

Hoang’s group launched its own public information campaign, combining information from the CDC on HIV and mpox. The messaging stressed that sex was the risky behavior and made sure to explain that light brushes or touches weren’t likely to pass the infection, he said.

Klausner thinks the CDC could have done better on messaging.

“By giving vague, nonspecific information and making comments like ‘everyone’s potentially at risk’ or ‘there’s possible spread through sharing a bed, clothing or close dancing’ … that kind of dilutes the message, and people who engage in risk behavior that does put them at risk get confused, and they say ‘well, maybe this isn’t really a route of spread,’ ” he said.

Cases came down, but why?

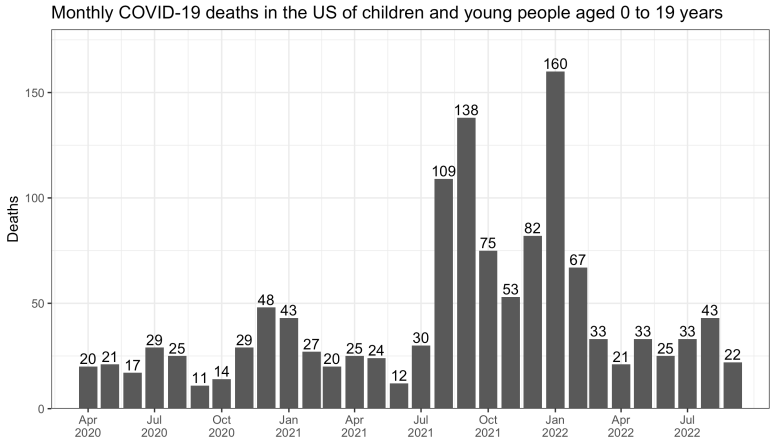

In July and August, when the US was reporting hundreds of new mpox cases each day, health officials were worried that the virus might be here to stay.

“There were concerns that there would be ongoing transmission and that ongoing transmission would become endemic in the United States like other STIs: gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis. We have not seen that occur,” said Dr. Jonathan Mermin, director of the CDC’s National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention.

“We are now seeing three to four cases a day in the United States, and it continues to decline. And we see the possibility of getting to zero as real,” he said.

At the peak of the outbreak, officials scrambled to vaccinate the population at highest risk – men who have sex with men – in the hopes of limiting both severity of infections and transmission. But no one was sure whether this strategy would work.

The Jynneos vaccine was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019 to prevent monkeypox and smallpox in people at high risk of those infections.

At that time, the plan was to bank it in the Strategic National Stockpile as a countermeasure in case smallpox was weaponized. The approval for mpox, a virus closely related to smallpox, was tacked on because the US had seen a limited outbreak of these infections in 2003, tied to the importation of exotic rodents as pets.

Jynneos had passed safety tests in humans. In lab studies, it protected primates and mice from mpox infections. But researchers only learn how effective vaccines are during infectious disease outbreaks, and Jynneos has never been put through its paces during an outbreak.

“We were left, when this started, with that great unknown: Does this vaccine work? And is it safe in large numbers?” Mermin said.

Beyond those uncertainties, there wasn’t enough to go around, and infectious disease experts feared that a shortage of the vaccine might thwart any effort to stop the outbreak.

So public health officials announced a change in strategy: Instead of injecting a full dose under the skin, or subcutaneously, they would inject just one-fifth of that dose between the skin’s upper layers, or intradermally.

An early study in the trials of the vaccine had suggested that intradermal dosing could be effective, but it was a risk. Again, no one was sure this dose-sparing strategy would work.

Ultimately, all of these gambles appear to have paid off.

Early studies of vaccine effectiveness show that the Jynneos vaccine protected men from mpox infections. According to CDC data, people who were unvaccinated were almost 10 times as likely to be diagnosed with the infection as those who got the recommended two doses.

Men who had two doses were about 69% less likely, and men with a single dose were about 37% less likely, to have an mpox infection that needed medical attention compared with those who were unvaccinated, according to the CDC.

Mermin says studies have since showed that the vaccine worked well no matter if was given into the skin or under the skin – another win.

Still, the vaccine is almost certainly not the entire reason cases have plunged, simply because not enough people have gotten it. The CDC estimates that 2 million people in the United States are eligible for mpox vaccination. Mermin says that about 700,000 have had a first dose – about 36% of the eligible population.

So it’s unlikely that vaccination was the only reason for the steep decline in cases. CDC modeling suggests that behavior change may have played a substantial role, too.

In an online survey of men who have sex with men conducted in August, half of participants indicated that they had reduced their number of partners and one-time sexual encounters, behaviors that could cut the growth of new infections by 20% to 30%.

If that’s the case, some experts worry that the US could see monkeypox flare up again as the weather warms.

“The party season was during the summer, during the height of the outbreak, and we’re in the dead of winter. So there’s a possibility that behavior change may not able to be sustained,” said Gregg Gonsalves, an epidemiologist at the Yale School of Public Health.

Although we’re clearly in a much better position than we were last summer, he says, public health officials shouldn’t make this a “mission accomplished” moment.

“Now, put your foot on the accelerator. Let’s get the rest of these cases,” Gonsalves said.

Work isn’t over

Mermin says that’s exactly what the CDC intends to do. It isn’t finished with the response but intends to switch to “a ground game.”

“So much of our work in the next few months will be setting up structures so that getting vaccinated is easy,” he said.

Nearly 40% of mpox cases in the United States were diagnosed in people who also had HIV, Mermin said. So the CDC is going to make sure Jynneos vaccines are available as a routine part of care at HIV clinics and STI clinics that offer pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, for HIV.

Mermin said officials are also going to continue to go to LGBTQ festivals and events to offer on-site vaccinations.

Additionally, they’re going to study people who’ve been vaccinated and infected to see whether they remain immune – something else that’s still a big unknown.

Experts say that’s just one of many questions that need a closer look. Another is just how long the virus had been spreading outside Africa before the world noticed.

“We’re starting to see some data that suggests that asymptomatic infection and transmission is possible, and that certainly will change how we how we think about this virus and and risk,” said Anne Rimoin, an epidemiologist at the Fielding School of Public Health at UCLA.

When researchers at a sexual health clinic in Belgium rescreened more than 200 nasal and oral swabs they had taken in May 2022 to test for the STIs chlamydia and gonorrhea, they found positive mpox cases that had gone undiagnosed. Three of the people reported no symptoms, while another reported a painful rash, which was misdiagnosed as herpes. Their study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

“Mild and asymptomatic infections may have indeed delayed the detection of the outbreak,” study author Christophe Van Dijck of the Laboratory of Medical Microbiology at the University of Antwerp in Belgium said in an email to CNN.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

While researchers tackle those pursuits, advocacy groups say they aren’t ready to relax.

Hoang says Equality California is pushing the CDC to address continuing racial disparities in mpox vaccination and treatment, particularly in rural areas.

He’s not worried that gay men will drop their guard now that the emergency has expired..

“We’ve learned that we have to take health into our own hands, and I do think that we will remain vigilant as a community for this outbreak and future outbreaks,” Hoang said.

Health - Latest - Google News

January 31, 2023 at 08:04PM

https://ift.tt/lyXsAwP

Mpox is almost gone in the US, leaving lessons and mysteries in its wake - CNN

Health - Latest - Google News

https://ift.tt/CVkWIHf