People who were infected almost two decades ago with the virus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) generate a powerful antibody response after being vaccinated against COVID-19. Their immune systems can fight off multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants, as well as related coronaviruses found in bats and pangolins.

The Singapore-based authors of a small study published today in The New England Journal of Medicine1 say the results offer hope that vaccines can be developed to protect against all new SARS-CoV-2 variants, as well as other coronaviruses that have the potential to cause future pandemics.

The study is a “proof of concept that a pan-coronavirus vaccine in humans is possible”, says David Martinez, a viral immunologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It’s a really unique and cool study, with the caveat that it didn’t include many patients.”

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the sarbecovirus group of coronaviruses, which includes the virus that caused SARS (called SARS-CoV), as well as closely related bat and pangolin coronaviruses.

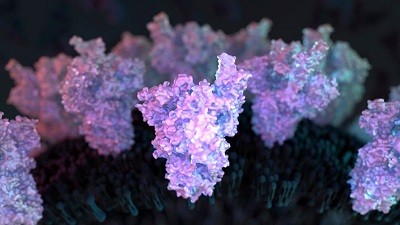

Sarbecoviruses use what are known as spike proteins to bind to ACE2 receptors in the membranes of host cells and enter them. They can jump from animals to humans, as they did before in both the current pandemic and the 2002–04 outbreak of SARS, which spread to 29 countries. “The fact that this has happened twice in the last two decades is strong rationale that this is a group of viruses that we really need to pay attention to,” says Martinez.

Neutralizing antibodies

Last year, Linfa Wang, a virologist at Duke–NUS Medical School in Singapore who led the latest study, went looking for people who had survived SARS to see whether they offered any clues about how to develop vaccines and drugs for COVID-19. He detected ‘neutralizing’ antibodies in their blood that blocked the original SARS virus from entering cells, but did not affect SARS-CoV-2 — which he found surprising, because the viruses are closely related.

But when Singapore rolled out the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine this year, Wang decided to interrogate how the SARS infection affected responses to the vaccine. What he discovered was striking. Eight vaccinated study participants, who had recovered from SARS almost two decades ago, produced very high levels of neutralizing antibodies against both viruses, even after just one dose of the vaccine.

They also produced a broad spectrum of neutralizing antibodies against three SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the current pandemic — Alpha, Beta and Delta — and five bat and pangolin sarbecoviruses. No such potent and wide-ranging antibody response was observed in blood samples taken from fully vaccinated individuals, even those who had also had COVID-19.

The researchers suggest that such broad protection could arise because the vaccine jogs the immune system’s ‘memory’ of regions of the SARS virus that are also present in SARS-CoV-2, and possibly many other sarbecoviruses.

Coronaviruses found in bats have the potential to cause future pandemics, so the fact that a broad spectrum of neutralizing antibodies is generated that protects against some of them “is encouraging”, says Daniel Lingwood, an immunologist at the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard in Boston. But researchers say it is not clear how long this protection lasts.

A vaccine that is widely effective against sarbecoviruses could be administered to the general population in high-risk areas close to animals that harbour them, limiting the potential spread of these viruses in people, adds Christopher Barnes, a structural biologist at Stanford University in California.

Which part of the virus

Barton Haynes, an immunologist at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina, says the study raises the question of whether a similar response could be generated if people vaccinated against COVID-19 were given a booster shot that targeted the original SARS virus. This might protect them against new variants of SARS-CoV-2 and other sarbecoviruses. Wang says preliminary studies in mice suggest that is possible.

But the latest study doesn’t identify exactly which sections of the viruses induce the broad immune response, something that would be needed to develop vaccines. That’s the “biggest question”, says Martinez. If it is a region of the virus that is present not just in sarbecoviruses, but in the entire group of coronaviruses, there is potential for creating a vaccine against all of them, he says.

Several research groups have identified specific antibodies that prevent SARS-CoV-2 and other sarbecoviruses from spreading in cells. Others are already working on pan-coronavirus vaccines, and have synthesized components that induce strong protection in monkeys and mice.

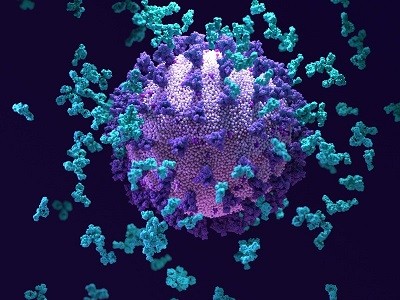

Haynes and his colleagues, for example, have developed2 a protein nanoparticle studded with 24 pieces of a section of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein called the receptor binding domain, a key target of antibodies. They found that in monkeys, the nanoparticle induced much higher levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 than did the Pfizer vaccine. It also induced cross-reactive antibodies against the original SARS virus and bat and pangolin sarbecoviruses.

Martinez and his colleagues have induced these widely reactive antibodies in mice, using a vaccine made from a combination of spike proteins from different coronaviruses3. But Martinez says the latest study suggests that this complex spike chimaera might not be necessary; a similar protective response could be induced simply by the original SARS virus’s spike protein.

Wang says he is already working on potential vaccines that target multiple sarbecoviruses, and he now hopes to find additional survivors of the 2002–04 SARS outbreak to conduct a much larger study, including testing their responses to other COVID-19 vaccines.

"virus" - Google News

August 19, 2021 at 04:04AM

https://ift.tt/3meLwhx

Decades-old SARS virus infection triggers potent response to COVID vaccines - Nature.com

"virus" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2OagXru

No comments:

Post a Comment